Picture a night shift in a spray drying plant. Moisture starts to drift. Operators tweak setpoints, wait for lab results, and hope the curve comes back. Some nights it does. Some nights it does not. The talk about “digital twins” in corporate slides can feel far away from that scene.

Yet this is exactly where a well-designed digital twin in powder processing can help. Not as a glossy dashboard, but as a practical companion that explains what the line is doing, and what will happen next.

Why Digital Twins Are Back On The Agenda

Most powder plants already have many of the ingredients. There is a historian full of process data. There are models from past projects. There are operators who know how the line really behaves.

What changed is that it is now easier to connect those pieces. Data platforms are more accessible. Simple models can run on ordinary servers. Process analytical technology is more familiar. As a result, digital twins are slowly moving from conference talks into day-to-day process work.

For powders, the interest usually starts in a few places:

-

Continuous blending and granulation

-

Spray drying and fluid bed drying

-

Pneumatic transport and silo discharge

-

Powder bed fusion and depowdering

These are steps where small shifts in conditions create large shifts in product behavior.

What A Digital Twin Looks Like On A Powder Line

In practice, a digital twin is not a full virtual factory. It is a living model of one real asset, kept in sync with plant data. Three elements matter.

First, there is a process model. It might describe residence time in a mixer, moisture removal in a dryer, or gas flow in a riser. The model does not need to be perfect. It needs to describe the main cause and effect links in the operating window.

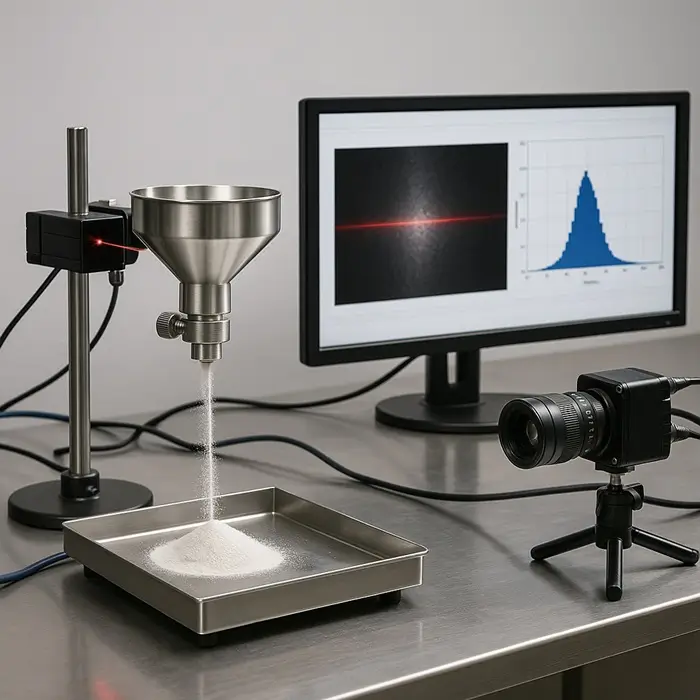

Second, there is a data link. Signals from feeders, temperatures, pressures, and simple at line measurements feed the model. The twin compares where the asset is today with where it is expected to go.

Third, there is a user view. Operators or engineers see a few key indicators. For example predicted moisture, blend uniformity, or risk of blockage. They also see what changes would move the process back to a safer zone.

When those three pieces work together, the twin stops being a buzzword. It becomes another instrument on the line.

Start With One Sharp Question – Start with the Why

Digital twins often fail because the starting question is fuzzy. “We want a digital twin of the whole factory” sounds ambitious. It is also almost impossible to maintain.

A sharper approach is to pick one question that everyone agrees hurts. For example:

-

Why does this dryer create more lumps on warm, humid days?

-

Why do we need so many blend samples before release?

-

Why do some PBF builds take hours to clean while others do not?

Once the question is clear, the scope narrows naturally. You know which unit operation to model. You know which outputs matter. You know what “success” looks like, in numbers.

That clarity also forces trade offs. A twin that predicts moisture to within 0.3 percent may be enough. You may not need full CFD of every air channel to get there.

Build On Data You Already Trust

The next step is to look honestly at current data. Many plants discover two things at once. They have more data than they thought. They trust less of it than they hoped.

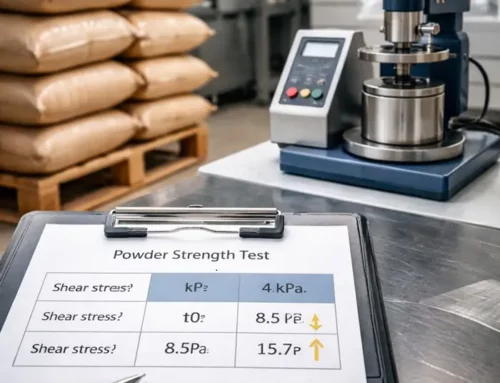

For a powder digital twin, basic signals often carry most of the value. Feeder trends show stability or drift. Temperatures and humidity reveal dryer stress. Pressure drops hint at deposits or build up. Lab tests confirm particle size, density, and moisture.

The key is to link those signals to real events. When did the silo block. When did the dryer foul. When did the blend fail content uniformity. A few good historical episodes teach the twin which patterns matter.

Only then does it make sense to add more sensors. Extra PAT is easier to justify when you can show how it will sharpen a model that already works in broad strokes.

Where Plants Actually See Payback

When you look across powder sites, early wins from digital twins tend to cluster around three themes.

One theme is stabilizing a chronic troublemaker. A twin that watches a spray dryer or blender can warn about drift earlier than the lab. It can suggest setpoint changes instead of forcing trial and error. Over time, the number of blocked lines and emergency cleanings falls.

A second theme is de risked scale up. Moving a formulation from pilot to full scale always brings surprises. A twin built on pilot data and simple models allows “what if” studies before expensive trials. Engineers learn which variables are sensitive, and where the safe window lies.

The third theme is training. New operators can replay past upsets in the twin. They see how the process responded when a feeder choked or air humidity spiked. This shortens the learning curve and makes handover between generations less painful.

None of these uses are glamorous. All of them move real money.

Getting Started Without A Big Program

The idea of a digital twin program can feel heavy. It does not need to start that way. A small, focused path often works better.

Choose one line where the business case is obvious. Map the process in a few honest diagrams. List the signals you believe. Collect a handful of good and bad runs. Then work with a small team to build a first model that explains those runs.

Treat this first twin as a pilot project. Put it in front of operators early. Ask what it explains well, and where it confuses. Adjust the user view until people understand it at a glance. Only then think about connecting more assets.

Over time, you can grow a family of digital twins across the plant. Each one will have a clear job and a defined owner. Together, they become part of how the site thinks about its powders, rather than a one time innovation project.